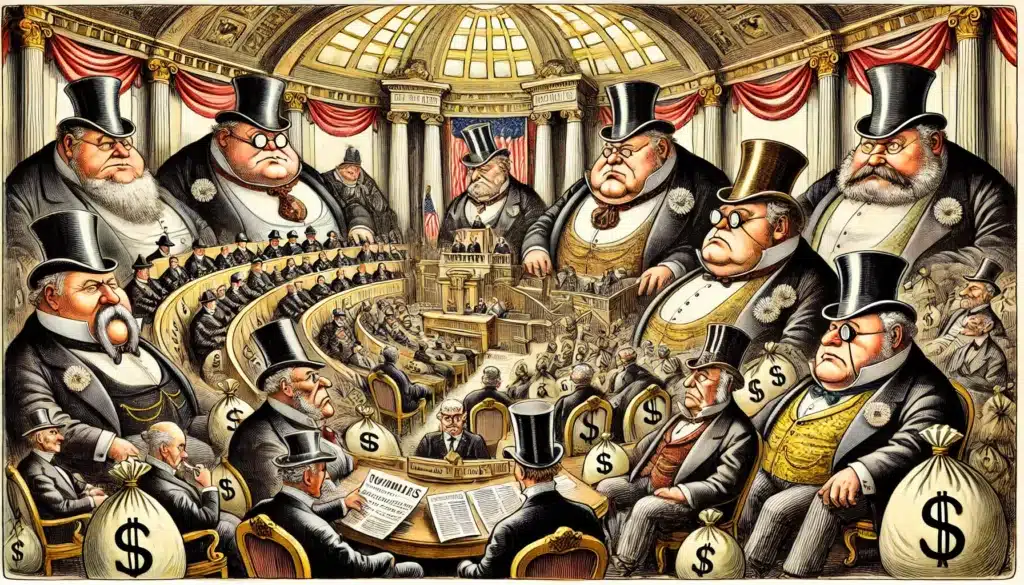

Meta’s retreat from truth heralds new world order

Meta’s dismantlement of its fact-checking programme marks a pivotal moment for news: what we choose to believe and how we understand our world. As someone who cut their teeth in ‘traditional’ PR, scrambling to verify facts for journalists to tight deadlines, this makes me really nervous.

The stark reality is that we’re witnessing not just a change in business model, but a fundamental restructuring of how information flows through our society. Meta’s decision to replace independent fact-checkers with user-generated “community notes” – following X’s controversial model – signals a retreat from institutional accountability that should concern us all.

In my early days working in a busy press office, we operated under the cardinal rule: never say “no comment.” This wasn’t merely internal policy; it was about preventing the spread of speculation and misinformation. The relationship between press office and news room was built on an unspoken contract – we would provide verified facts, and they would report them accurately. Every story published went through rigorous editorial processes: fact-checking, legal scrutiny, and multiple source verification.

But that world feels increasingly distant. Today’s digital landscape of social media platforms is shaped by what Pew Research calls “news influencers” – predominantly male, right-leaning commentators, of whom only 16% have any background in journalism. These digital pundits command audiences of hundreds of thousands, yet operate without the ethical framework that has guided traditional media for generations.

The timing of Meta’s announcement, just days before Trump’s return to the White House, speaks volumes. Mark Zuckerberg’s claim that third-party moderators were “too politically biased” comes after his November pilgrimage to Mar-a-Lago and Meta’s million-dollar contribution to the inauguration fund. The company’s rightward shift is further cemented by the appointment of prominent Republican Joel Kaplan to replace Sir Nick Clegg as global affairs chief, and UFC president Dana White – a close Trump ally – joining the board of directors. When Trump himself publicly suggests that Zuckerberg is “probably” responding to past threats, this isn’t merely about improving content moderation – it’s about currying favour with the incoming administration.

And that sends chills down my spine.

The cruel irony of our digital age is that in an era where humanity has instant access to more information than ever before, the quality of our understanding and conversation has plummeted. We carry in our pockets devices capable of accessing the sum of human knowledge, yet social media algorithms deliberately funnel us toward outrage rather than enlightenment. These systems aren’t designed to help us navigate this unprecedented wealth of information – they’re engineered to inflame and divide, pushing controversial content into our feeds because anger drives engagement, and engagement drives profit. With Meta now abandoning human fact-checkers and AI increasingly controlling these algorithms, we face a disturbing future where the greatest information revolution in human history could become nothing more than a self-perpetuating cycle of rage and misinformation. The very tools that promised to connect and inform us are being weaponised to divide and confuse.

Writing this, I find myself grappling with uncomfortable questions about truth and my own use of facts. Every press release I have ever written involves selecting certain truths to emphasise while downplaying others. But there’s a crucial difference between strategic communication and the wholesale abandonment of verification standards. Hand on heart, I have built a career based on a reputation for honesty, transparency and integrity.

The PR profession is governed by clear ethical standards and a formal complaints process. My own agency is a member of the Chartered Institute of Public Relations and we adhere to a comprehensive Code of Conduct that emphasises integrity, professionalism and public interest.

In the UK, media self-correction primarily occurs through regulatory bodies like the Independent Press Standards Office (IPSO) and structured regulatory frameworks that have evolved over time, particularly following the Leveson Inquiry into press standards.

The audience has gradually moved away from ‘legacy’ media and its, admittedly, imperfect checks and safeguards, towards platforms that lack the processes, history, and wisdom to handle their unprecedented influence. These platforms and those who run them are primarily motivated by profit, not public service.

Meta’s retreat from fact-checking isn’t just about one company’s policies – it’s a symptom of a broader shift in how our society determines truth. And that really matters. As we enter this brave new world of self-regulation, we must ask ourselves: if everyone’s a publisher, how do we know what’s true, who decides? And more importantly who will guard the guards?

The answer, troublingly, appears to be no one at all.